‘What have we done?’ – written by the co-pilot of the Enola Gay in his diary, as he witnessed the mushroom cloud of the atomic bomb spreading over Hiroshima.

August 6, 1945

In the Enola Gay

five minutes before impact

he whistles a dry tune

Later he will say

that the whole blooming sky

went up like an apricot ice.

Later he will laugh and tremble

at such a surrender, for the eye

of his belly saw Marilyn’s skirts

fly over her head for ever

On the river bank,

bees drizzle over

hot white rhododendrons

Later she will walk

the dust, a scarlet girl

with her whole stripped skin

at her heel, stuck like an old

shoe sole or mermaid’s tail

Later she will lie down

in the flecked black ash

where the people are become

as lizards or salamanders

and, blinded, she will complain

Mother you are late. So late

Later in dreams he will look

down shrieking and see

ladybirds

ladybirds

By Alison Fell

CONTEXT: The title of the poem indicates the date America dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima. This unprecedented move by America is said by some to have ended WW2, however the poem itself explores the guilty conscience of those involved in the bombings and refers throughout to time passing, as each stanza begins with the word ‘later’. The poem is written from a retrospective point of view, yet begins moments before the bomb is dropped, when the world was still oblivious to the idea of atomic warfare.

‘Enola Gay’ is the name of the Boeing B-29 Superfortress plane carrying the atomic bomb ‘Little Boy‘, and was named by pilot Colonel Paul Tibbets after his mother. The bomb was uranium-based and was untested during the Manhattan Project, unlike the second bomb (‘Fat Man‘) that was plutonium-based, and was dropped on Nagasaki three days after the Hiroshima bombing.

In the poem, Fell explores two aspects of the bombing; the aerial view of the pilots as they watched the event from the plane and their subsequent feelings of detachment, and also the suffering of the victims on the ground from the radioactive fallout.

Fell uses vivid imagery to show the three deadly stages of the bombing. The first is the ‘blast’ which produced the mushroom cloud. This is curiously compared to the iconic image of Marilyn Monroe in her white dress as it gets ‘blasted’ by the air from the subway grating.

The second stage is the fire storm and the ‘black rain’ that occurred after the blast. The fire storm is shown through the ‘the scarlet girl’, whose skin has been stripped off from the heat of the bomb. The black rain is compared to bees ‘raining’ over white flowers, which symbolises the white-hot heat of the fire as it burns the people at ground-zero.

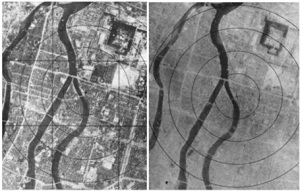

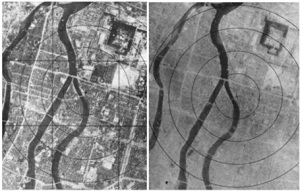

The third stage is the radioactive fallout, which is again shown through the girl whose body is being consumed by the cancerous radiation as she lies down in defeat. Other victims are also hinted at, and compared to ‘lizards’ and ‘salamanders’, who are well-known for shedding their skin. In ancient times salamanders were believed to be immune to fire, but this is false. Fell uses this image in an ironic way, as none of the victims survived the blast. In fact, photos taken by American pilots before and after the attack show a Hiroshima that was quite literally ‘wiped off’ the map.

Photos of Hiroshima taken before and after the bombing.

The final stanza refers to a popular nursery rhyme called ‘Ladybird, Ladybird, fly away home‘. The rhyme contains the lines: ‘your house is on fire and your children are gone’, which links with Hiroshima being on fire and how all the children are dead or gone. The rhyme also refers to a girl called Ann, who survives by hiding under a baking pan. This could be linked to the girl in the poem whose skin has fallen off and is barely alive.

TONE/ MOOD: The poem is written in a conversational tone with lines like ‘the whole blooming sky’ where the word ‘blooming’ could be to swear or curse in colloquial language (slang). There is as sense of irony throughout the poem, as Fell uses inappropriate imagery to compare to the horrors of war. The mushroom cloud resembles Marilyn Monroe’s skirts and the fire from the bomb is compared to ‘apricot ice’. The poet is constantly challenging our view of the events with such images and this gives the poem a tone of absurdity. The realities of war are caricatured, or made smaller, which mirrors how mankind cannot cope with the scale of the atrocity and seeks to ‘shrink’ the consequences down to a manageable size. In the last stanza, this is represented by how the burning humans take on the shape of ladybirds in the dreams of the pilot.

RHYME/ RHYTHM: The poem has no regular rhyme or rhythm. This irregularity matches the feeling of confusion created in the poem.

KEY IMAGERY/ IDEAS:

* The ‘Enola Gay‘ – There is a constant reference to female figures. The plane ‘Enola Gay’ is named after the pilot’s mother and carries not only her offspring (the pilot himself) but also the bomb ‘Little Boy’, the brain-child of America. The plane symbolises America itself, which as a country is referred to as ‘the motherland’. She leads her brave sons to make history and conquer Japan. The dropping of the bomb signifies her ‘giving birth’ to a new and terrible age of warfare, where the ‘sons’ of one country annihilate the ‘sons’ of another.

* Marilyn Monroe – The burst of the bomb is compared to the iconic figure of Marilyn Monroe with her flying skirts. This is sexually charged imagery, where motherland America is seen to stand astride Japan in a victory pose that is both a mockery and a taunt. It is a provocative pose, and the pilot gets aroused by the explosion the same way he would if looking at this picture of the sex icon. It promotes a boosted sense of virility for America as the ‘doer’ and ‘winner’; which is in total odds with Japan, whose population suffered from years of radiation exposure which caused sterility.

We could also argue that Monroe’s skirts that ‘fly over her head forever’, could signify a turning point for America and the world, where things will never be the same again. It also paints the image of a woman forever violated; of a woman who is perhaps so ashamed of what has happened, that she is ‘hiding’ her face from the very event she has given birth to.

* the ‘Scarlet girl’ – The word ‘scarlet’ suggests a girl who is perhaps sexually promiscuous, which links to the image of Marilyn Monroe and sexual violation. Her skin hangs off her body in the same way that Monroe shows her skin in the provocative photo. The plane can also be connected to this idea as the name ‘Enola Gay’ is written over its body like a tattoo.

* Lizards/ Salamanders – The victims are compared to lizards and salamanders which is not only belittling, but also draws further ties with the shedding of skin, which these creatures are known to do. Salamanders were once believed to be immune to fire, however this is not true. It is ironic that Fell should use this imagery, as the victims had no protection against the catastrophe that befell them.

*Colours – These are used frequently in the poem. The most common are black, red, orange and white; colours that are associated with death, danger, surrender and war. The white is mentioned when Monroe’s skirts ‘surrender’ to the bombing; the red to the girl whose skin strips away to reveal raw muscle underneath (danger, blood, desire); the black to the ash that represents death shrouding the city and the orange to the ‘apricot ice’ fire storm that rages after the mushroom cloud.